Many disorders begin early in life, and early psychiatric diagnosis is possible [1]

Early psychiatric diagnosis is all too rare

Median delays among cases eventually making contact ranged from 3.0 to 30.0 years for anxiety disorders, from 1.0 to 14.0 years for mood disorders, and from 6.0 to 18.0 years for substance use disorders.

…early-onset disorders were associated with lower probabilities of initial treatment contact in most countries. One explanation for this finding may be that minors need the help of parents or other adults to seek treatment, and recognition is often low among these adults unless symptoms are severe… In addition, child and adolescent- onset mental disorders may be associated with normalization of symptoms or development of coping strategies (e.g., social withdrawal in social phobias) that interfere with help-seeking later in life.

…our earlier analyses of the U.S. data revealed that even those with severe and impairing disorders have substantial delays in initial treatment contact…[2]

Young people are less likely to seek help if they:

- are experiencing suicidal thoughts and depressive symptoms;

- hold negative attitudes toward seeking help or have had negative past experiences with sources of help; or

- hold beliefs that they should be able to sort out their own mental health problems on their own.[3]

Early psychiatric diagnosis is possible

Initial treatment contacts appear to be fastest for mood disorders, perhaps because these disorders have been targeted in some countries by educational campaigns, primary care quality improvement programs, and treatment advances… On the other hand, the longer delays for anxiety disorders may be due to the earlier age of onset of some conditions (e.g., phobias), fewer associated impairments, and even fear of providers or treatments involving social interactions (e.g., talking therapies, group settings, waiting rooms)…

Women have been shown in prior research to be faster than men at translating nonspecific feelings of distress into conscious recognition that they have emotional problems, perhaps explaining the significantly higher rates of initial treatment contact by women in some countries…

More recent cohorts were also significantly more likely to make eventual treatment contact, perhaps suggesting a positive outcome of programs recently attempted in some countries to destigmatize and increase awareness of mental illness, of screening and outreach initiatives, of the introduction and direct-to-consumer promotion of new treatments, and of expansion of insurance programs…[2]

Young people are more inclined to seek help for mental health problems if they:

- have some knowledge about mental health issues and sources of help;

- feel emotionally competent to express their feelings; and

- have established and trusted relationships with potential help providers.[3]

Early psychiatric diagnosis is kind

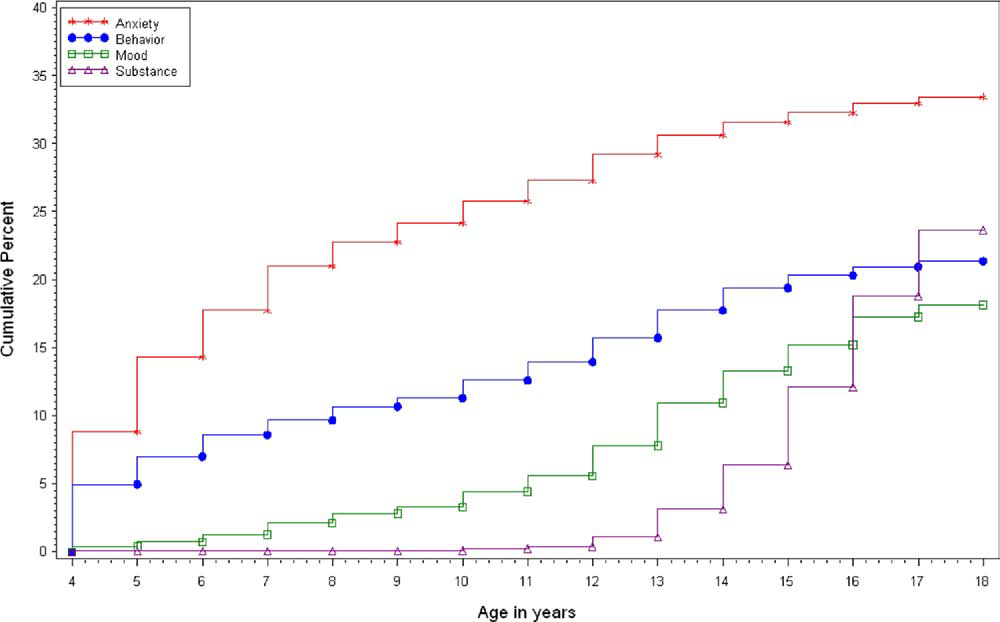

Lifetime Prevalence of Disorders

| Any anxiety disorder Any mood disorder Any impulse-control disorder Any substance use disorder Any disorder |

28.8% 20.8% 24.8% 14.6% 46.4% |

[4]

Depression is a major human blight. Globally, it is responsible for more ‘years lost’ to disability than any other condition. This is largely because so many people suffer from it — some 350 million, according to the World Health Organization — and the fact that it lasts for many years. (When ranked by disability and death combined, depression comes ninth behind prolific killers such as heart disease, stroke and HIV.) [5]

…preclinical, epidemiologic, and trial data… suggest that even milder disorders, if left untreated, lead to greater severity, additional psychiatric comorbidity, and negative social and occupational functioning…[2]

- Merikangas, Kathleen Ries, et al. “Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A).” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 49.10 (2010): 980-989.

- Wang, P. S., et al. “Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative.” World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) 6.3 (2007): 177-185.

- Rickwood, Debra J., Frank P. Deane, and Coralie J. Wilson. “When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems.” Med J Aust 187.7 Suppl (2007): S35-S39.

- Kessler, Ronald C., et al. “Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.” Archives of general psychiatry 62.6 (2005): 593-602.

- Smith, Kerri. “Mental health: a world of depression.” Nature 515.7526 (2014): 181.