Public attention vs. media coverage of Vietnam war [1]

Progressive skew didn’t win up through the 1890s

…crisis alone need not spawn Bigger Government. It does so only under favorable ideological conditions, and such conditions did not exist in the 1890s. Acting with substantial autonomy, governments even in a representative democracy may… refuse to accept or exercise powers that many citizens would thrust upon them.

American governments in the twentieth century, impelled by a more “progressive” ideology, readily accepted—indeed eagerly sought—expanded powers.[2]

Progressive skew starts with journalists’ worldviews

“Now the thing that God puts in a man that makes him a creative person makes him very sensitive to social nuances and that sort of thing. And overwhelmingly—not by a simple majority, but overwhelmingly—people with those tendencies tend to be on the liberal side of the spectrum. People on the conservative side of the political spectrum end up as vice presidents at General Motors.”

Individuals with strong political views will accept lower pay to do the type of reporting they believe in. Professionalism and peer review increase autonomy and independence in many fields.

…85 percent of Columbia Graduate School of Journalism students identified themselves as liberal, versus 11 percent conservative…

The journalists who voted for a major party candidate in presidential elections between 1964 and 1976 overwhelmingly went for Democrats: Lyndon Johnson 94 percent, Hubert Humphrey 87 percent, and George McGovern and Jimmy Carter 81 percent each.[3]

Progressive skew spins stories that show government people as heroes

Although people commonly suppose that news organizations report just the facts, journalists typically tell stories about current events. A report on a house fire, an earthquake, a factory closing, or a battle is actually a story about the event. It is no coincidence that we call news reports “stories.”

During times of foreign crisis and the early stages of a war, there is likely to be near-unanimous support for the war effort among the denizens of official Washington. The crucial expansion of government power can occur without the news media’s presenting the case against that expansion (for want of a prominent source).

…reporters place great reliance on government officials as sources. Members of the opposing party typically provide the “other” point of view, which limits the range of coverage.

Government… serves as a personalized hero, offering new policies to solve society’s problems. Thus, for example, a fiscal stimulus package to revive economic activity provides a happy ending to a story about a recession.[4]

Progressive skew tilts coverage towards government, and all the more during “crises”

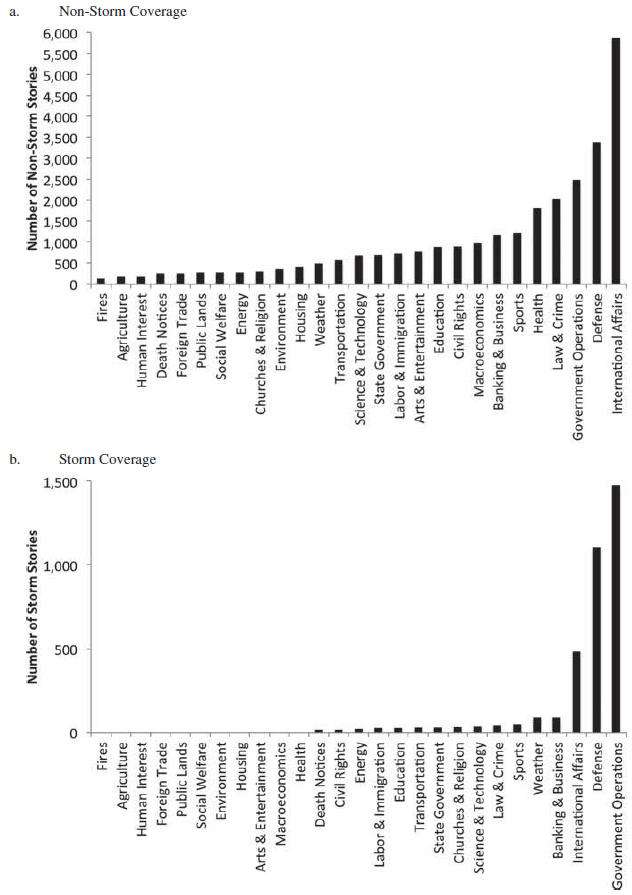

…in this article media storms are operationalized as instances of a strong increase (≥150%) in attention to an issue/event that lasts at least 1 week and that attains a high share of the total agenda (≥20%) during at least that week.

New York Times front page story policy areas for 1996-2006:

Coverage is skewed, especially during media storms.[5]

Progressive skew of media “crises” is followed by disproportionally-large government actions

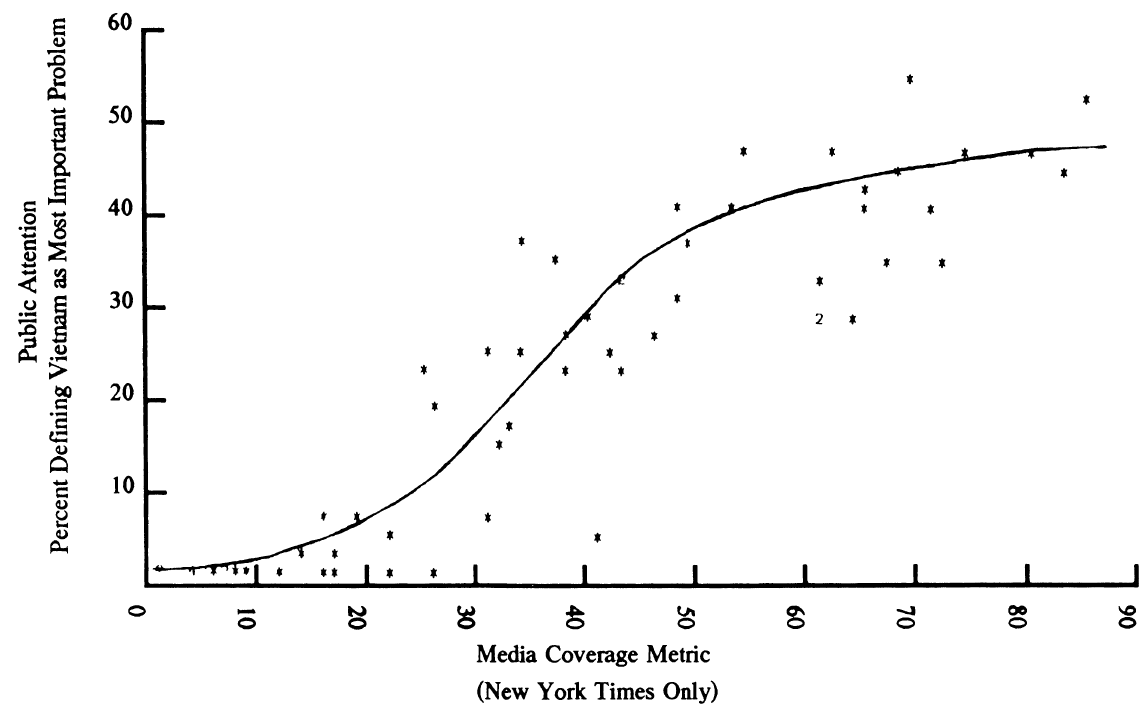

We first replicated the well-known and general linear effect of media attention on political attention: when media attention goes up, politics follows.

More importantly, we found that, once in media storm mode, media attention has a significantly stronger effect on congressional hearings than when not in storm mode. Our findings—which were the first results of an empirical, systematic examination of incoming information—support the notion that punctuated political attention is due to a nonlinear processing of incoming information.[6]

- Neuman, W. Russell. “The threshold of public attention.” Public Opinion Quarterly 54.2 (1990): 159-176.

- Higgs, Robert. Crisis and Leviathan: Critical episodes in the growth of American government. Oxford University Press, 1987, pp. 78-79.

- Sutter, Daniel. “Can the media be so liberal? The economics of media bias.” Cato Journal 20.3 (2001): 431-431.

- Sutter, Daniel. “News media incentives, coverage of government, and the growth of government.” The Independent Review 8.4 (2004): 549-567.

- Boydstun, Amber E., Anne Hardy, and Stefaan Walgrave. “Two faces of media attention: Media storm versus non-storm coverage.” Political Communication 31.4 (2014): 509-531.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, et al. “The nonlinear effect of information on political attention: media storms and US Congressional Hearings.” Political Communication (2017).