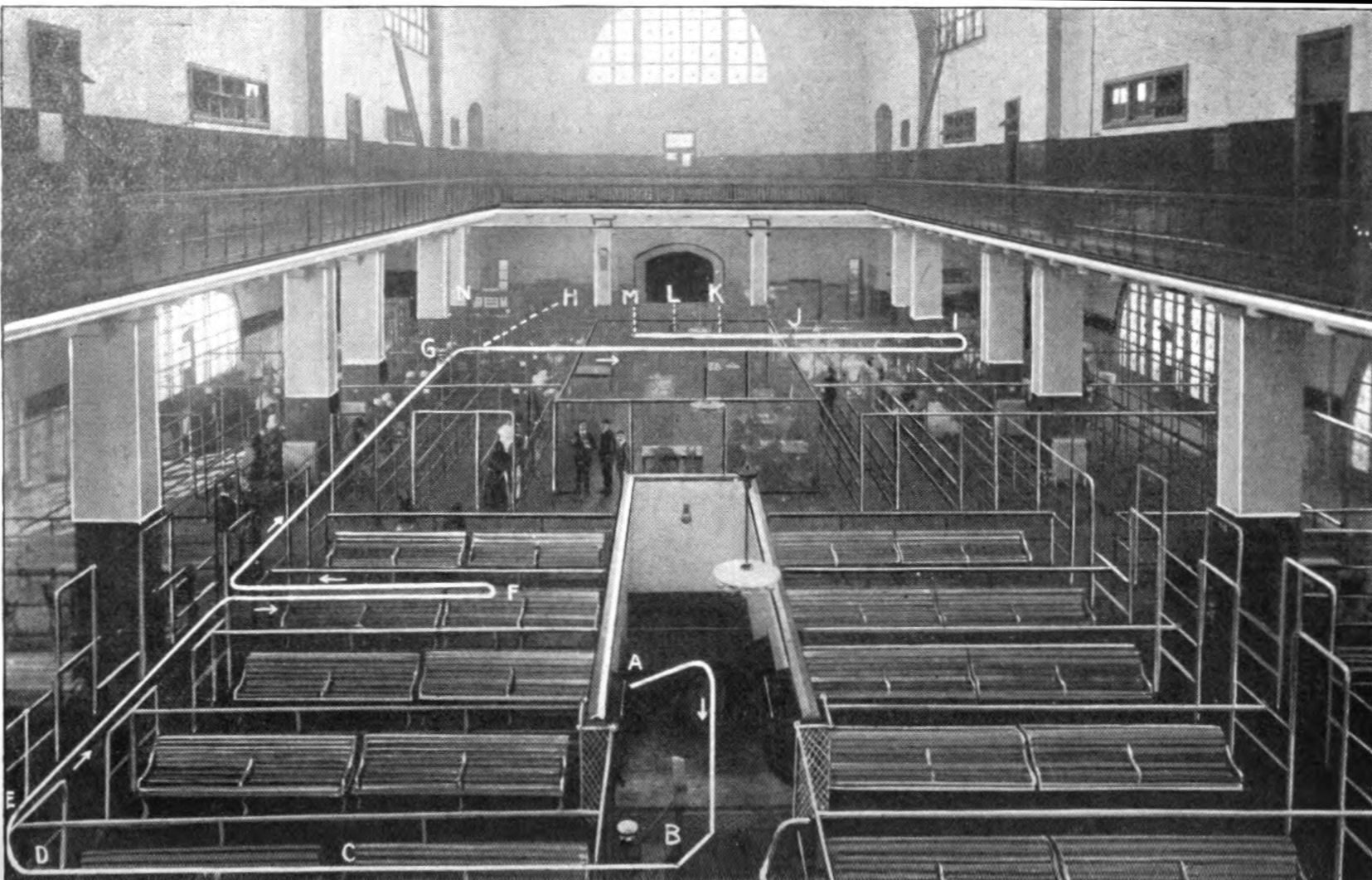

The Immigrant’s Track Through Ellis Island

A. Immigrants landed from barges enter by these stairs.

B. Surgeon examines health tickets.

C. Surgeon examines head and body.

D. Surgeon examines eyes. Suspects go to left for further examination.

E. Female inspector looking for prostitutes.

F. Group enters and sits in pen corresponding to ticket letter or number.

G. Inspector examines on twenty-two questions.

H. Into special inquiry court.

I. Stamping railroad ticket orders.

J. Money exchange and telegraph office.

K. To railroad pen.

L. To New York pen.

M. To the ferry and New York.

N. Telegraph office.[1]

Armed, on the one hand, with the Public Charge Law of 1882, which excluded those who seemed like invalids or paupers and, on the other hand, with the Anti-Contract Labor Law of 1885, which excluded those who seemed like they came with a promise of work, federal administrators quickly assumed the task of erecting an elaborate inspection apparatus for individuals seeking to enter the United States.

These two contradictory laws, developed in different historical circumstances, operated with equal legal force on Ellis Island, as inspectors selectively admitted immigrants who seemed able-bodied and defenseless.

“To get the fullest grasp,” Brandenburg explained in his book, “we must become immigrants ourselves and re-enter our own country as strangers and aliens.” Disguised as “Italian,” then, this peculiarly self-reflexive journalist convincingly documented aspects of passing through Ellis Island.

Much of the legal work of Ellis Island occurred aboard the ships that took immigrants across the Atlantic. On board, Brandenburg recounted how federal law required ships’ manifests to match precisely the name of every immigrant who appeared before inspection or the United States authorities would “exact a fine of $200.”

Likewise, immigrants began rehearsing the federal inspection process on the ships. Not only did those who had already been to the United States tell stories about inspection to others on board, but prior to sailing some had prepared written rehearsals that they consulted in transit: “I saw more than one man with a little slip of notes in his hand carefully rehearsing his group in all that they were to say when they came up for examination.”‘

At first, inspectors thought the two “were dagoes all right,” but they grew suspicious at Brandenburg’s wife who, as one inspector claimed, was “the first woman I have ever seen in the steerage with such well-kept finger-nails.” Clean finger-nails drew attention, because they upset the inspector’s expectations of Italians as dirty people, and so her fingers suggested that she was perhaps trying to attract attention – the kind of attention allegedly sought by prostitutes.

On Ellis Island itself, the couple experienced little trouble passing through immigration controls: “Our papers were all straight, we were correctly entered on the manifest, and had abundant money, had been passed by the doctors, and were properly destined to New York, and so were passed in less than one minute.”

Brandenburg’s account reveals how inspection effectively encouraged each immigrant to appear meek, yet able-bodied in front of inspectors enforcing contradictory laws. In other words, inspection favored those who appeared defenseless and duty-minded.[2]

- Brandenburg, Broughton. Imported Americans: The Story of the Experiences of a Disguised American & His Wife Studying the Immigration Question. Stokes, 1904. pp. page facing 227, 227.

- Anthes, Louis. “The Island of Duty: The Practice of Immigration Law on Ellis Island.” New York University Review of Law & Social Change 24 (1998): 563-600.