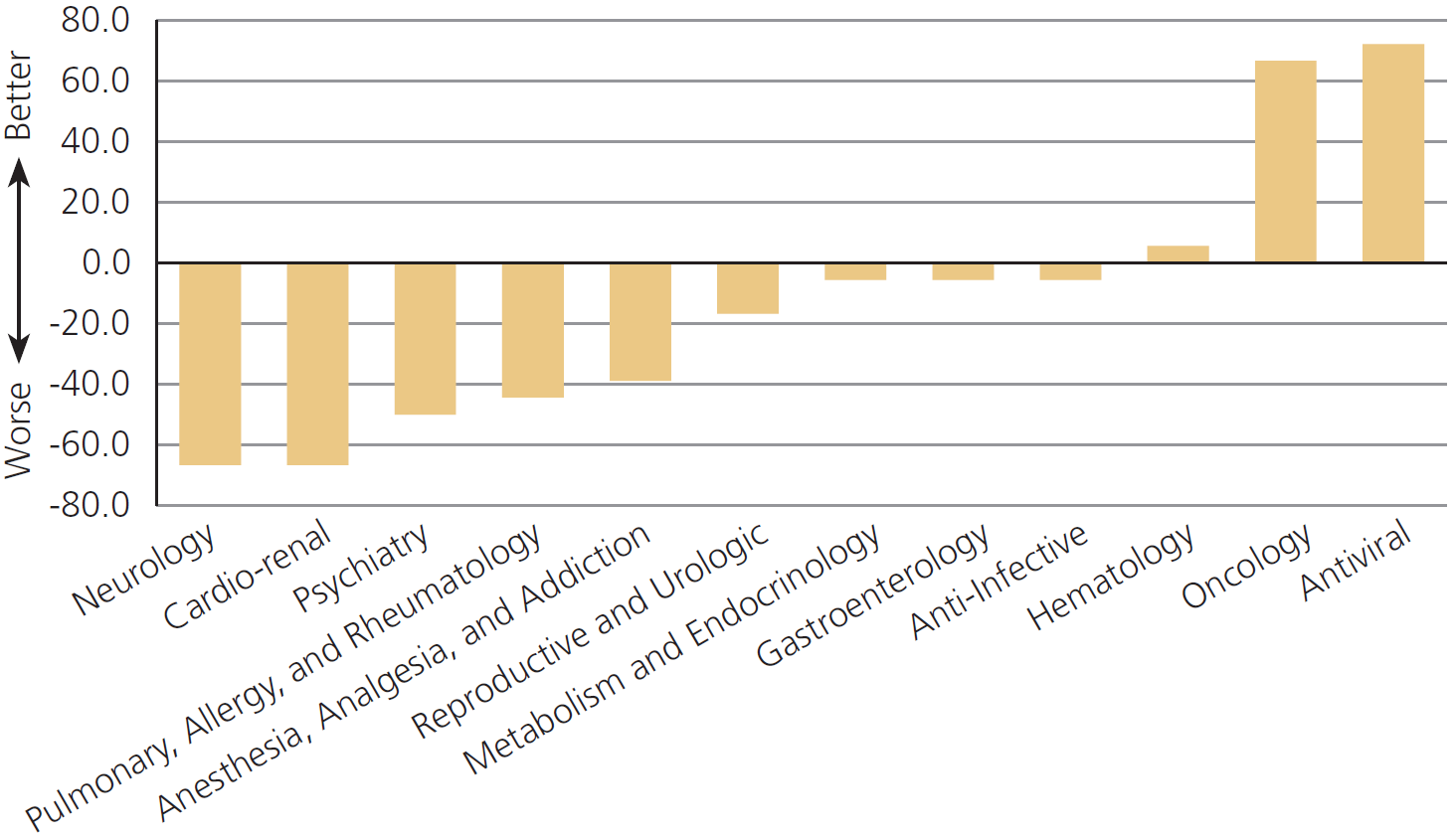

The FDA performs worse on drugs for pain, psychiatry, and allergies,[1] but off-label prescribing helps patients in these areas especially

Off-label prescribing provides the majority of therapeutic uses of drugs

…once a drug has been permitted for a specified use, physicians may legally prescribe it for other uses called ‘off-label’ uses. …off-label prescribing provides a window onto a world with substantially less FDA regulation.

Off-label prescribing is regulated by the judgments of doctors, medical researchers, industry, the patient community, and patients. The off-label experience testifies to the fact that much knowledge about efficacy and safety of drugs is produced outside the FDA regulatory apparatus.

…from the 29 new drugs permitted onto the market in 1988 there were 143 substantial new uses that were developed over the subsequent five years. Importantly, 57% of the new uses were discovered by clinicians working in the field.

Drugdex and other compendia collect information about off-label indications and in effect certify thousands of drug uses quite independently of the FDA.

Off-label prescribing brings new therapies and tailored therapies

Viagra (sildenafil citrate) was initially intended to treat angina…

…when older men reported its unusual side-effect it became a blockbuster treatment for erectile dysfunction.

After being approved for that use, sildenafil citrate was also found to be useful in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension for which it was prescribed off-label. Since the market for pulmonary hypertension is considerably smaller than that for erectile dysfunction it is quite likely that had sildenafil citrate not already been permitted for erectile dysfunction it would not have been profitable to research and develop the drug for pulmonary hypertension.

This is the problem of drug loss – drugs that are never researched and developed because the permitting process is too expensive to justify the effort.

Off-label prescribing bypasses this process and brings new treatments to patients.

…when a drug reaches the end of its patent life, no firm ever has a strong incentive to undertake clinical trials despite the fact that off-label prescribing may be common.

What works well in some patients does not work well in others. Off-label prescribing increases a physician’s arsenal. A larger arsenal is useful when standard treatments fail, as they often do. When standard treatments fail it is not irrational to try treatments with less evidence of efficacy especially when the disease is life-threatening or the drug to be prescribed has a strong safety profile.

…off-label use is most common in the absence of strong scientific support in the treatment of pain, psychiatric problems and allergies. In each of these cases, standard treatments often fail, the disease in question may be difficult to diagnose even when symptoms are plain, patients are heterogeneous, and physicians and patients can with considerable safety run a series of personal drug trials to find the best match.

Off-label prescribing would help more if the FDA was less-controlling and if information was shared more-widely

The post-marketing surveillance system in the United States is weak. Analysis of data from Medicare as well as from large HMOs could be used to improve prescribing both on and off-label, especially if access to the data was widespread.

More generally, FDA currently works on a paternalistic model: one choice to rule them all. But another model, what I have called the Consumer Reports model, would meet the needs of diverse health-care consumers much better.

Consumer Reports does not try to replace consumer choice. Instead, by carefully evaluating and testing new products and providing this information to readers, Consumer Reports helps consumers to make better choices.[2]

Every drug available for prescription in the United States must have gone through at least phase I clinical trials. Phase I trials examine a drug for toxicity in healthy volunteers and establish that the drug meets a minimum level of safety.

Drugs used in FDA-approved ways have also been through phase II and phase III “efficacy” trials. Studies… consistently find few benefits and large costs.[3] …no such requirement exists for new uses of old drugs.

…the reform proposal… would resolve the inconsistency by dropping efficacy requirements, so that people would be freer to produce, sell, and market drugs, even for initial uses… Those with the best knowledge of the particular circumstances and with the strongest incentives to do right by the patient would then have expanded options of utilizing therapies that may be very beneficial.[4]

…a less paternalistic FDA would provide more information to patients and doctors, but it would also leave more choices in their hands because only patients and their doctors have the particular knowledge that allows each patient to be treated as an individual.

…innovation often arises from the bottom up rather than from the top down.[2]

- DiMasi, Joseph A., Christopher-Paul Milne, and Alex Tabarrok. AN FDA REPORT CARD: Wide Variance in Performance Found Among Agency’s Drug Review Divisions. Project FDA Report 7. Manhattan Institute, 2014.

- Tabarrok, Alex. “From off-label prescribing towards a new FDA.” Medical Hypotheses 72.1 (2009): 11-13.

- Tabarrok, Alexander T. “Assessing the FDA via the anomaly of off-label drug prescribing.” The Independent Review 5.1 (2000): 25-53.

- Klein, Daniel B., and Alexander Tabarrok. “Do Off‐Label Drug Practices Argue Against FDA Efficacy Requirements? A Critical Analysis of Physicians’ Argumentation for Initial Efficacy Requirements.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 67.5 (2008): 743-775.