[1:113-114]

[1:113-114]

Trade restraint was a response to innovators

…starting with the early 1900s and continuing through the 1920s, American business underwent quite radical changes in the development of major new industries and new methods of manufacture and product distribution.[1:16]

…Schumpeter concluded that price competition is not the most significant factor to which firms have to respond. In his view, “it is not that kind of competition which counts but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization… competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage and which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives.” [1:17]

Trade restraint was pilot-tested during World War I

Businessmen, recalling the managed harmony of the war years, confronted the intensely competitive 1920s with hopes of realizing a more durable and predictable setting in which to conduct business. Firms that viewed the processes of change as threats to their positions began organizing resistance.[1:18]

The systemwide benefits of maintaining openness in competition—with no legal restrictions on freedom of entry into the marketplace or on the terms and conditions for which parties could contract with one another—were being rejected by business organizations more concerned with the survival of individual firms and industries.[1:18]

As a consequence, business leaders expressed an increasing desire for the maintenance of conditions of equilibrium that would help preserve the positions of existing firms.[1:16]

Trade restraint moved big business from competing economically to competing politically

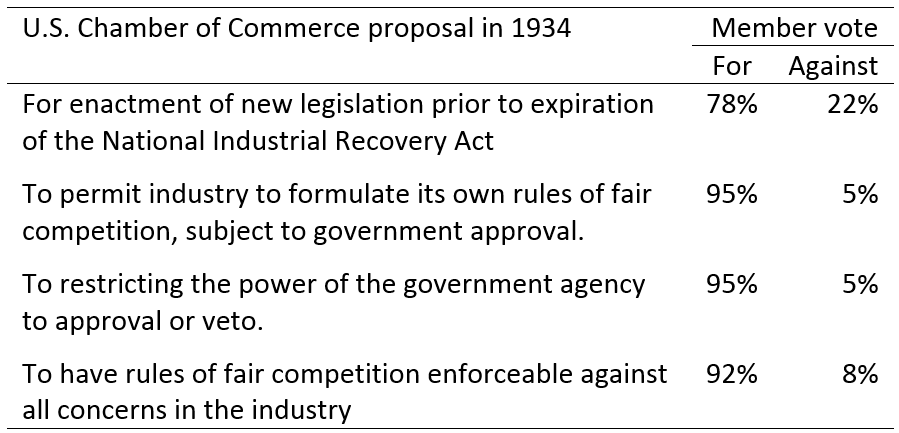

One finds industry leaders and trade groups railing constantly against the “price cutter,” the “cutthroat” competitor, and the entrepreneurial interloper who dared to “invade the territory” of an established competitor. Such efforts invariably began with voluntary methods of “self-restraint.” When voluntary approaches failed to produce the desired stability, many businessmen—mindful of the advantages experienced under the War Industries Board—sought to effectuate this spirit of “cooperation” through politically backed programs designed to fashion a greater degree of centralized business decision-making. Characterizing their proposals as “industrial self-regulation,” business spokesmen and trade associations worked to secure for themselves a diluted competitive environment that would not be threatening to their interests. Such political efforts to control trade practices led, ultimately, to the enactment of the National Industrial Recovery Act…[1:19] The purpose of such legislation… was to repress and stabilize competitive conditions-to ossify industries and restrain those influences that represented the threat of change.[1:121]

[I]ndustrial concentration is not the inevitable outgrowth of economic and technical forces, nor the product of spontaneous generation or natural selection. In this era of big government, concentration is often the result of unwise, manmade, discriminatory, privilege-creating governmental action. Defense contracts, R and D support, patent policy, tax privileges, stockpiling arrangements, tariffs and quotas, subsidies, etc., have far from a neutral effect on our industrial structure. In all these institutional arrangements, government plays a crucial, if not decisive, role. Government, working through and in alliance with “private enterprise,” becomes the keystone in an edifice of neomercantilism and industrial feudalism. In the process, the institutional fabric of society is transformed from economic capitalism to political capitalism.[1:212]

- Shaffer, Butler D. In Restraint of Trade: The Business Campaign Against Competition, 1918-1938. Bucknell University Press, 1997.