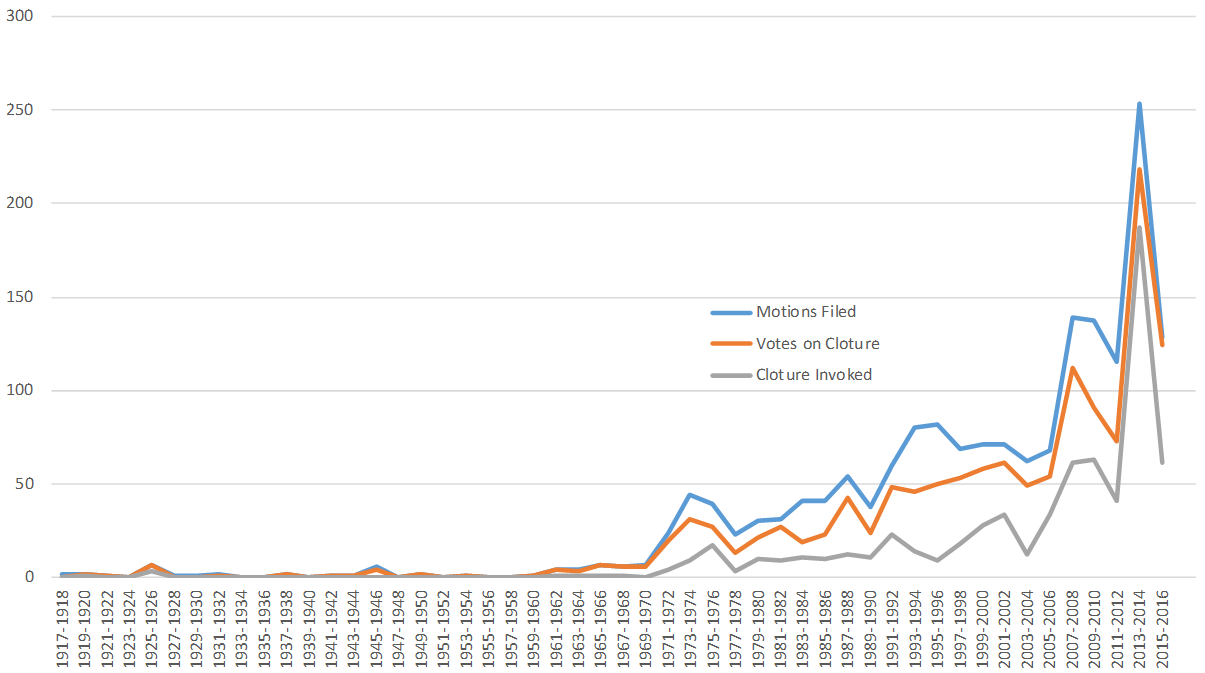

Senate action on cloture motions [1]

Unconstitutional filibuster/cloture violates the Constitution’s core practical purpose, and plain text

…the core purpose of the new Constitution was to jettison the Articles and the “[g]reat inconveniences had… been experienced in Congress from the article of confederation requiring nine votes in certain cases.”

Delegates… fixed representation in the House according to population, while giving each state an “equal voice” in the Senate.

Article I, Section 3 specifies that the Vice President shall serve as President of the Senate, “but shall have no Vote, unless they be equally divided.” Put simply, Article I, Section 3 shows that the Framers meant for final Senate action on proposed matters to hinge on the vote of a legislative majority, with the Vice President’s vote to determine whether an aye-voting or nay-voting majority exists in the event that the Senators themselves are “equally divided.”

Article I, Section 7 states that “[e]very Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate… shall…. be presented to the President. The critical term in this clause is “passed,” which Americans understood at the time of the framing… to hinge on “the act of a majority of a quorum” in the absence of “specific limitations… found in the Federal Constitution” itself. This understanding finds support in established practice at the time of the framing, Noah Webster’s dictionary of 1828, and the two English legal dictionaries that existed in 1787.

…the Constitution specifies five and only five instances in which the chambers of Congress are to act by supermajority vote. This list… demonstrated understanding—noted by Joseph Story nearly two-hundred years ago—that “departure from the general rule, of the right of the majority to govern, ought not to be allowed but upon the most urgent occasions.”

…Article II’s unitary textual treatment of judicial-branch and executive-branch nominees counsels against countenancing a different treatment of the two groups with regard to permissible forms of senatorial “consent,”…

…Article VI requires Senators… to take an oath to support the Constitution, and so they must honor the limits it imposes.

Unconstitutional filibuster/cloture was confirmed illegal during ratification

In Federalist No. 22, Hamilton decried… “If a pertinacious minority can controul the opinion of a majority… the sense of the smaller number will overrule that of the greater…”

…Federalist No. 54 assured the ratifying community that “[u]nder the proposed Constitution, the federal acts… will depend merely on the majority of votes in the Federal Legislature…”

In Federalist No. 58, Madison… concluded that… supermajority voting rules would invite “an interested minority [to] take advantage of [such rules] to screen themselves from equitable sacrifices to the general weal or … to extort unreasonable indulgences.” “It would no longer be the majority that would rule; the power would be transferred to the minority.”

Federalist No. 58 spoke of the risks of supermajority voting rules “[i]n all cases where justice or the general good might require new laws to be passed.”

Federalist No. 75… found fault with “all provisions which require more than the majority of any body to its resolutions.”

Unconstitutional filibuster/cloture was Progressively slipped into place

…the earliest Senates permitted a majority of members to halt debate on any pending matter pursuant to what was called the “Previous Question Rule.”

…the Senate abandoned the Previous Question Rule in 1806… instead for a system that in effect required unanimous consent to end debate on pending matters.

A true filibuster—pursuant to which dissenters openly take and hold the Senate floor—threatens to saddle dissenters with opprobrium by exposing their actions for all to see, making vivid their willingness to throw a wrench in the workings of the upper chamber. …the need to filibuster in this way had exactly this deterrent effect.

…senators utilitized speech-based delays only in exceptional cases for the remainder of the nineteenth century.

…targeted use of obstructionist speechmaking triggered ameliorative reforms, including the Senate’s replacement in 1917 of its unanimous-consent policy with a rule that authorized cloture by a vote of two-thirds of the members in attendance.

…during most of the twentieth century, filibusters focused on civil rights bills, which were bitterly denounced by southern segregationists. …the high water mark of obstructionist speechifying came when southern Senators occupied the floor for seventy-four days in an effort to block passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

…in 1975 the Senate adopted its current rule, which requires sixty votes to end debate, regardless of the number of Senators present. In addition, during this same time frame, the chamber embraced a “two-track” system… in which delays in acting on one matter would not block the Senate from moving forward with other business… The modern stealth system leads to no floor debate.”

Unconstitutional filibuster/cloture keeps unconstitutional big government ratchet-locked in place

One effect of these changes is that the use of Rule XXII to block action by Senate majorities has soared to unprecedented heights in recent years—indeed, to dizzying heights. As a result, “almost all significant legislation” now needs the support of sixty Senators…

…the Cloture Rule… has come to contravene the fundamental principle of legislative majoritarianism established by our founding charter.[2]

- “Senate Action on Cloture Motions.” Senate.gov. www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/cloture_motions/clotureCounts.htm. Accessed 28 Jan. 2017.

- Coenen, Dan T. “The Filibuster and the Framing: Why the Cloture Rule is Unconstitutional and What to Do About It.” Boston College Law Review 55.1 (2014): 39-92.